Should higher education providers be bound by a duty of care towards their students?

- Issy Clarke

- Aug 20, 2023

- 4 min read

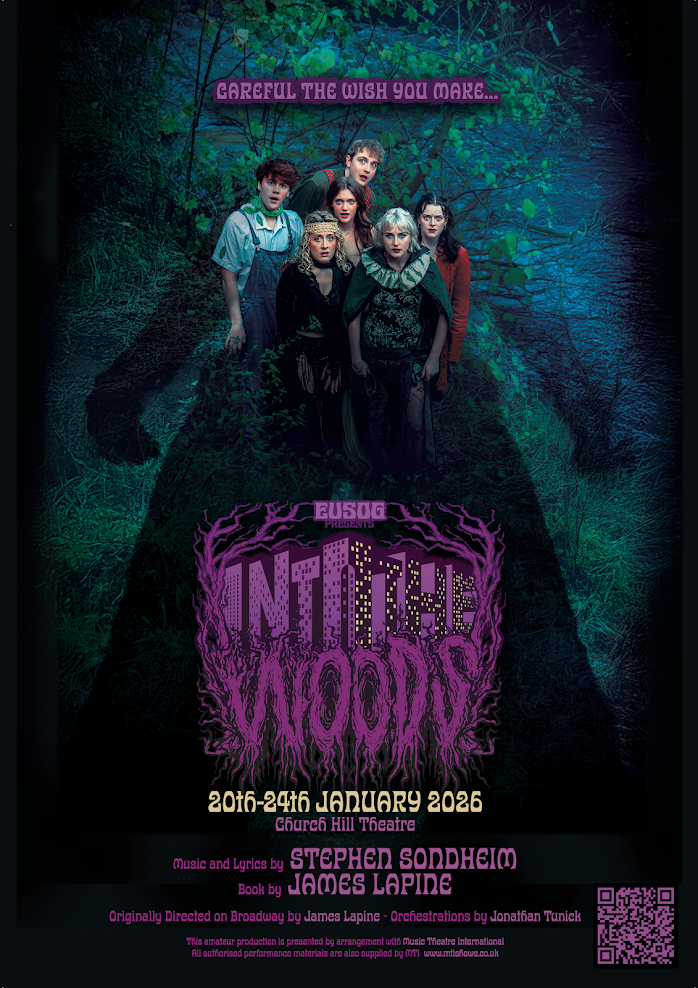

Illustrations by Megan Le Brocq

As the summer break approaches its mid-point, many students will be casting their eyes towards the next academic year. This year’s incoming Freshers will be receiving the ritualistic influx of information about fresher’s week, course options, sports, and societies. Somewhere amidst this barrage of leaflets and emails will be information about the mental health and wellbeing services available at the university.

The University of Edinburgh talks a lot about mental health, but its approach can often seem to prioritise style over substance. Posters pronouncing the mood-boosting effects of taking the stairs instead of the lift are plastered across the library. From time to time puppies are brought into university buildings to support students stressed with exams. Yet if you want an appointment with one of the university’s counsellors, prepare to be stuck on a three-month long waiting list at best — or at worst, to be in receipt of an email advising you to pay for private treatment.

In recent months, the national debate surrounding mental health support within higher education has crystallised upon the proposal to introduce a statutory duty of care. If passed into law, universities would be legally required to protect students from mental or physical harm, bringing them closer to the safeguarding model in place in schools. The campaign for such a law change has been led by the parents of Natasha Abrahart, the university of Bristol student who died by suicide in April 2018.

Currently universities are bound by a general duty of care to ensure that they do not cause harm to students while performing its functions. A statutory duty of care would take this a step further, penalising not only harm incurred by a university’s actions, but also by its failure to act.

Universities UK, the body which represents 140 university providers, recognises the need for there to be more support for students struggling with poor mental health, but resists the argument that a duty of care represents the best solution. The group believe that poor mental health is a UK-wide problem, rather than university-specific, and that a duty of care would represent neither a ‘proportionate’ nor a ‘practical’ approach to an issue which, they claim, exists more within the remit of the government and the NHS. Universities are not ‘parents’ and do not manage student’s wider lives. A comprehensive psychiatric function, in short, is simply not within their scope.

Their argument fails to sufficiently recognise that some features of UK higher education system contribute to creating an environment where vulnerable young people can experience a deterioration in their mental health, often beneath the radar. Most first-year students are only 18 and have moved away from home for the first time, often to an unfamiliar city, to start a degree with very little in-person contact and hours of unstructured time to fill. The dual blows to the student experience of the pandemic and strike action have further hollowed out the opportunities for contact between students and staff. The keystone of the student support model is the personal tutor system – yet many students meet with them just once a year and carry out most communication, with both support staff and tutors, over email. There is nothing inherently wrong with this, but it is worth recognising the monumental shift this represents for 18 year olds used to the trifold support network of teachers, parents, and friends. The transition to a world where most communication is carried out sporadically and remotely is often a significant adjustment. Tellingly, in a survey carried out by The Tab earlier this year, just 12% of students agreed that they felt their university was handling mental health well.

Universities must take on more responsibility for student mental wellbeing — even if this does not go as far as the implementation of a legal duty of care. Steps have been taken in the right direction. Recently the Secretary of State for Education set a 2026 deadline for UK universities to sign up to the advisory Student Mental Health Charter (which Edinburgh is yet to join).

Crucially, there needs to be far more honesty injected into conversation about higher education in Britain. At the moment, excessive focus attached to academic league tables leads to many schools pushing students to apply for the most selective institutions. There is a limited discussion of what the student experience entails on a day to day basis — the lack of structure and face to face teaching, and the limited student support. Schools, in partnership with universities, need to be transparent with prospective applicants about what they can realistically expect when they get to university. Some may be best advised to delay or forgo the experience altogether. But young people and their parents can’t be expected to make the best and safest decision if they are not being provided with all the information.

The issues are complex, but the message couldn’t be clearer in essence: universities need to be at the front line of developing better policies that support young people. As the tragic case of Natasha and other student suicide victims illustrates, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Comments